UTOPIA. Hidden Therapies

Exhibition runs from 27 November 2020 to 16 January 2021

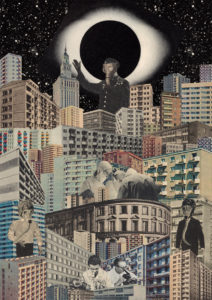

Mateusz Szczypiński’s utopian collages invite a sense of déjà vu – an urban landscape suspended in cosmic space is strangely familiar. The artist deconstructs the logic of history in order to develop its alternative and potential models.

“My works address topics related to memory and its impact on the present. They concentrate especially on the question of memories which are constantly imprinted in people, which ‘overgrow’ them and help them weave their own inner, intimate asylums.” This approach resembles Aby Warburg’s search for visual testimonies that carry traces of memory, evoked by means of long-standing visions in pursuit of capturing human mentality.

The dystopia created by Mateusz Szczypiński in his collages is not an apocalyptic world that falls into ruin. On the contrary, it proliferates and piles up dangerously. Individual collages offer its alternative visions. The non-linear and ahistorical character of these representations makes it difficult to establish their context, disturbing the sense of time. We are facing a similar situation today, when the past from before the pandemic seems extremely distant, although not even a year has passed; time has become strangely extended.

The narrative develops on a number of levels – it is a game of simultaneous, separate, but mutually related scenes set in specific social frames. Combined freely, they begin to resemble a Dadaist collage, brimming with humour and absurdity. Like a flâneur, the viewer’s gaze wanders around the architectural maze in search of life in-between. The scale of the metropolis is overwhelming, the figures that populate it appear stuck in urban spaces. Confined to our homes during lockdown, we may identify ourselves with this experience in a certain way, while the medical motifs and the impression of information chaos in the collages bring to mind our present day situation.

article from Contemporary Lynx magazine:

Mateusz Szczypiński is an artist who made his debut with a series of paintings and collages which made strong references to the traditions of art history. With time, however, his works have started to feature abstract elements which have slowly come to dominate his entire body of work. His latest work can be seen in Frankfurt as a part of the open group exhibition — Contemporay Art from Poland.

Agnieszka Jankowska-Marzec

On things common and uncommon.

Maybe we’re here only to say: house, bridge, well, gate, jug, olive tree, window — at most, pillar, tower … but to say them, remember, oh, to say them in a way that the things themselves never dreamed of existing so intensely.

We are here, and Mateusz Szczypiński seems to echo Rilke, not only to attempt to name the nature of things, but also to keep discovering the character of objects, a character which is contrary to the banal role usually ascribed to it. This question about our sensitivity to things results largely from a nostalgia that Szczypiński experiences. It is a nostalgia both for the world of things that he may have dreamt of as a child, and those emerging unexpectedly from the archives of his memory: the control screen on the TV, the first computer pixel images, and tailor’s patterns and crosswords which could always be found in most Polish homes. Further on we encounter associations with the unarticulated childhood dreams about space, about galaxies far, far away; pulsating planets and stars; and memories of filling crosswords in by hand, in times when using pen and paper rather instead of a mouse was commonplace. Objects, ready materials and drawn or painted forms, all of which seem to exude a retro atmosphere. They express nostalgia for a world that not only is slowly becoming extinct, but also constitutes a clear reference to the classics of avant-garde. “Devotio moderna”, “Black Square” bring to mind “the golden age” of violent changes and re-evaluations of art, the impact of which we still experience to this day. Therefore, the stance of artists who were active at the beginning of the last century and who posed questions on the presence of objects in paintings, about the forms and methods of joining and juxtaposing ready-made elements in art is familiar to Szczypiński. An interest in art history, which is not limited to the reception of the works of the first avant-garde, is a common experience of Szczypiński’s generation of artists born in 1980s. Fascination with the past means both the reinterpretation of the works of the masters of modernism, as well as researching the ins and outs of their own memory. Because they are not interested in merely repeating the stylistic of the works created several decades ago, but rather in revealing new contexts and possibilities of reading the heritage of modernity, filtered through their private experiences.

The strategy of recycling used by the artists is not only about the viewer and the artist taking a sentimental journey into the past. In his works he uses old crosswords and tailor’s patterns found in flea markets. The crosswords are filled in — the puzzle had been solved, the mystery is gone and maybe that is what everything is about…We should approach them as a visually attractive material, a certain formal proposal, which allows the artists to contradict its initial function and meaning. Szczypiński is also interested in purely formal matters — pasting, painting over, filling in and combining into surprising combinations, as well as the free associations raised by the “materials” used by him. After all, crosswords are not only word puzzles, but also hybrids created as a result of merging two different specimens in order to obtain a new species.

Colloquially: a crossing is a place where several roads or possibilities meet, where we make a decision about the direction we shall take.

When the artist invites the viewer to think about the “language” he uses: of colours, lines or writings, they become first and foremost a visual sign, a being coming into dialogue with other elements on the canvas. Szczypiński employs already used materials, as if looking for signs of their initial users, pondering over the passing of time, just like Rilke in his Duino Elegy (IX) cited at the beginning: Praise the world to the Angel, not the unsayable: you can’t impress him with glories of feeling (… ) So show him a simple thing, fashioned in age after age that lives close to hand and in sight. Tell him things.(…) Show him how happy things can be, how guiltless and ours, how even the cry of grief decides on pure form, serves as a thing, or dies into a thing: transient, they look to us for deliverance, we, the most transient of all.

Written by Agnieszka Jankowska-Marzec

Translated by Ewa Tomankiewicz

Edited by Mannika Mishra

MATEUSZ SZCZYPIŃSKI

Somewhere Between – Our Matters

opening: 1st February 2014 (Saturday), 18:00

exhibition continues until 15th March 2014

The project “Somewhere Between” comprises two exhibitions by Mateusz Szczypiński and Benjamin Bronni in Stuttgart and in Warsaw. Below you can find a photo report from the first part of this project that take place at Galerie Parrotta Contemporary Art in Stuttgart.

Both artists were born in the mid-1980s and even though they grew up in two different countries, they share references to a common visual tradition which each of them is working through in his own way. Despite different media – Benjamin’s works are mostly spatial installations, while Mateusz deals mainly with painting – their creative methodologies betray a robust common denominator.

Each of the two shows will also feature interventions by the other artist, thus opening the possibility of confronting their dissimilar approaches to the legacy of abstract art on the one hand, while on the other – of discerning certain formal similarities in their practice. Fascination with Modernism, shared by Bronni and Szczypiński, marks a point of departure for each artist’s individual investigations. They become Benjaminian “materialist historians”, who construct an image of the contemporary on the ruins and partly forgotten snippets of the past. They are trying to analyse and determine anew the mutual relations and dependencies between forms, hues, surfaces, compositions and space. They launch attempts to decipher them and locate again in a new place in the contemporary reflection on painting, sculpture, or installation. One of their adopted methods consists in the use of modules, marked for their repetitiveness and seeming predictability.

Bronni develops his works on the basis of a rigid geometrical form which enters a space and operates as the basis and the building material of the subsequently generated objects. The artist experiments with materials, texture, layers, permeation of forms and infinite potential of their simplification or development. His works adopt the form of multi-layered, abstract mosaics composed of precisely cut and glued MDF board or wood. Aesthetically, Bronni’s practice refers to the avant-garde sculpture and object, however, it never boils down to a mere reference to historic forms. Formal liaisons occur alongside distortions and disobedience to modernist paradigms. Bronni plays with both empty and developed spaces, geometric and organic forms alike. Many of his objects are also marked for their frontal character. The specific location and orientation of the composition towards the viewer determines not only the inner structure of the works, but also deliberately relates them to the viewer.

Szczypiński’s practice is not far-removed from the Dadaist gesture which extracts an object from its usual configuration and shifts it onto new layers of interpretation. His art does not match any specific narration, maintaining a position between painting and collage, the past and the future. Szczypiński’s method consists in beginning anew, rebounding from chaos and the inability to control it. This strategy leads him, among others, to attempts at a sort of “arrangement” achieved, among others, through the introduction of geometrical forms and application of the module – a repetitive element, like a single building within the urban tissue, or a fragment of a trivial newspaper crossword, whose structure quite unexpectedly reveals unlimited potential of generating visual sets.

Curator: Dobromiła Błaszczyk

Organisers: Fundacja Lokal Sztuki, lokal_30, Galerie Parrotta Contemporary Art in Stuttgart

Media patronage: Contemporary Lynx, Magazyn Szum

Project co-financed by the Foundation for Polish-German Cooperation

Dobromiła Błaszczyk, “Our Matters” , Warsaw 2014

Buildings piling one upon another, dating back to various periods, having different functions. Photographs of buildings compiled from newspaper cut-outs from magazines issued through the years in various parts of Poland, as well as around the world. The structure of Mateusz Szczypiński’s painting conveys an ever-growing urban fabric. It brightens up the sky above the city with its energy. New elements are being built on top of the ruins and remains of the past. A palace, a cinema, a block of flats; an acrobat, a soldier, a model, a politician; a chimney, a telescope, a car. Motifs that seem oddly familiar to us yet exotic at the same time. Looking at them we gain the impression that we have already seen all of these things before. Crowds of people passing by on the streets every day, anonymous, varied and yet alike at the same time. Faces that are unique, but somehow covered with masks. Painted, artificially stylised, playing mysterious roles in this strange performance, where progress is a mask of civilisation, but underneath we are still the same, governed by primeval needs. The pattern of our rituals has altered, but their essence is unchangeable.

Nicolas Bourriaud states that artists, “perceive the History as a pile of wreckage, more or less enigmatic, which the artist must piece together into a logical structure”, in order to build “the genealogy or archeology of our age”[1]. According to him, the reading of history should begin with ruins and left-overs; the objects that are witnesses of history, the images that fill the earth and constitute our heritage. Some of them are “chosen” and called works. Others are invisible, or forgotten, or their primeval meaning has been distorted. These are the outskirts of memory, where Walter Benjamin’s “materialist historian” is right now; in this case, an artist who perceives the “symptoms of our present situation” in the past.

The generation of artists born in the eighties, like Mateusz Szczypiński, slowly capture materials thrown away on the beaches/outskirts of history. Perhaps the reason for this lies in the fact that this is the “borderline” generation, whose childhood coincided with a period of transformation, a reshaping of the world which wanted to cut itself off from recent history and was clearly opening up to the future. Maybe this is the reason these artist subconsciously turn to the past, to seek something else, something that for them will be a clear point of reference in the present. Something that would define them.

Szczypiński’s works are close to the Dadaist gesture of giving an object the rank of art by removing it from its everyday surroundings and placing it in new interpretative planes. It is possible to discern the roots in arte povera, which reached for left-overs, rubbish, a poor degraded object, which by witnessing real life has been raised to the rank of art by a demiurge-artist. Mateusz searches for everyday newspapers, fashion magazines, city postcards, people’s photographs at antique fairs, auctions of unwanted things. All of these objects are forgotten, devoid of qualities that initially defined and individualised them. They become nameless images, witnesses of the past. From these collected and merged elements of a forgotten world the artist generates an image of the present…

Collage

It seems that the techniques of collage and photomontage used by Szczypiński (otherwise connected to the Dadaist search for the image of reality), perfectly convey the nature of his quest. However, it is not about digital print-outs or multimedia productions but about objects created as a result of laborious, manual work – a palpable and unique contact of the artist with his work’s subject matter. What is more, this interest in collage is not only caused by a fascination with this medium and its aesthetics, but by the fact that this technique accurately conveys today’s outlook on art and the world within which it functions. Diversity, the use of quotations, and peculiar eclecticism are the most characteristic traits of contemporary culture. There is not one defined rule and norm of conduct. The technique of collage is one of many means to reach the goal, which is to express the nature of present times.

History

What methods could help us to understand the nature of present times? One of the trails is surely Jung’s psychoanalysis, where we are shaped – next to the ego, the persona and the soul – by our individual experiences, acquired and hidden in the unconscious, and by the sphere of the unconscious common to all mankind (the collective unconscious); the matters which cannot come to awareness (these are archetypes and instincts). Szczypiński on the one hand reaches for the elements/ information/ images acquired by everyone in the course of our education and passing years; on the other hand he uses archetypes, images and elements functioning from the beginning of mankind which form our identity even if we are not aware of it. He attempts to bring out images that comprise our heritage, that make us what we are. Only when we are aware of the elements that form our reality and by being here and now, we will be able to take a step further. As Nicolas Bourriaud wrote in The Angel of the Masses: “the manner in which we invent the narrative of our life depends on the concept of our own identity, of the image that we have forged of ourselves”[2].

This is not about moving forward or about an evolution. These categories were closely connected to the modernist/ avant-garde idea of progress and passing of time. Nowadays, at the beginning of the 21st century, these are notions that have been negated and rejected many times by subsequent generations of artists. Is it possible to talk about evolution now? Or perhaps about directions explored by the artist?

Bourriaud, in the above-mentioned text, states that “all works of art generate as many routes into the future as into the past; they are a place of temporal bifurcation, opening up paths which ultimately will be followed by other artists, at the same time allowing us to reread the past in the light of the intuition that directed their creation”[3]. Szczypiński reaches for materials he only knows from stories, books and films. For him, the world of the thirties, forties and sixties is strange and unknown; thus as intriguing as modern times or the middle ages. There are the subsequent stories filtered through literature, propaganda, national narratives, the interests of the state and of the individual, advertising slogans and images that attempted to capture and highlight these narratives. Szczypiński is not in favour of any of them. He uses the past and attempts to interpret it for himself again, to take out those elements from it which in an overall perspective may be forgotten; yet they are important for him here and now. Time and time again he chooses, analyzes and interprets subsequent motifs, images and compositions. He examines the extent to which a given image is clear for a contemporary person. It is worth mentioning that Szczypiński studied art history. His knowledge of art has an outcome in his works, in the way he observes visual heritage. At the same time, a kind of rebellion is perceptible. His actions are not a scientific search for objective facts, but their contestation, a play on convention, sometimes with indulgence, and sometimes in opposition to “official” interpretations. However, he is mostly interested in the viewer’s perception of an art work, and in the visual sign which eventually turns into an art work. What is more, he creates new associations which bring along new, unusual combinations. By showing them to the viewer, he interferes with the image of history, and changes our visual habits.

Szczypiński’s works are kind of Benjaminian point, where “yesterday” becomes “today”. By not being attributed to a particular narrative history, and by placing himself between painting and collage, past and future, he can distance himself from subsequent artistic ideologies and a certain pre-ordained history of the image.

Mateusz Szczypiński attempts to relate to the contemporary image of art in the present by starting afresh, from a chaos of pressing meanings and images. He collects and combines hundreds of images, symbols and signs that often do not match chronologically. They are spread over various corners of history, partly hidden, forgotten, and absorbed by others; and thanks to this, like organs transplanted from a donor, they continue living in a different form.

This attitude can be associated with Samuel Beckett’s later opinions revolving around the problem of the boundlessness of mixed plots and objects which are not arranged hierarchically. Beckett advocated collecting all outer world experiences, the inrush of various stimuli, and giving them a form which will gain the quality of a finished and simple structure. In his view of painting and art in general, he states that “what we have before us (…) is simply a mess”[4]. However, it is not a “mess” which will have an outcome, in which we will be able to find the meaning. Moreover, for Beckett this chaos is ubiquitous, also in the context of art. He wrote in the 1960s that “there will be a new form, a form which will allow for chaos and will not say that it is something different. Form and chaos remain separated. Chaos does not lead to the form. That is why we are being absorbed by the form itself. As it exists as something separate from the material that it ought to encompass. Finding a form that would encompass the mess is a task for an artist today”[5].

Fifty years later these words have become current. From chaos, from the total inability to control and encompass the whole of rush of images and information, the 21st century artist starts his slow search afresh. We should ask whether achieving this goal (if there is any) is possible at all. Isn’t Szczypiński doomed to defeat while trying to grasp this chaos in subsequent forms by using scraps of previously found history? Is it at all possible, knowing that diversity and heterogeneity lie at the basis of the uniqueness of the present times? It resembles an attempt to gather and assemble pieces of tampered glass into a new whole, but these tiny pieces constantly fall apart into even smaller elements in the hands of the artist. What is there left to do? Perhaps one should come to terms with adversities, understand their nature and continue working despite and thanks to these limitations. As Beckett wrote in Worstward Ho: “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try Again. Fail again. Fail better”.

Artists of the eighties do not act globally as they acknowledge this inability. They are not usually engaged in critical-social-political contexts, but they focus on the individual. They delve into problems which bother them and which are important to their inner development. Post post-modernism, art appears an apparent freedom that makes everything relative and subjective. There are no pre-ordained rules. And precisely this itself becomes a kind of obstacle. By playing a game with no rules, artists begins to lose their sense of time, and then they apply certain constraints on themselves. With these constraints appear rules, within which artists can move around and dwell on them without fear of what awaits them at the end of their artistic way.

Following the thought of Louis Althusser one needs to act “with nothing, but its unique ideas”[6], as it is the only possibility to overcome emptiness and powerlessness. So what method does Szczypiński chose? He chooses painting as his “weapon” – a traditional technique indeed, operating with two-dimensional canvas, paint, brush and paper. And exactly these apparently already exploited means serve him as a tool and a language to create something new.

He also turns to art history, a subject he studied along with painting. In spite of stressing that he does not consider himself an art historian, his way of thinking about painting, its analysis and comparative evaluation, as well as a reflection on the art work runs subconsciously through all stages of his work. In the chaos of information, countless numbers of images flashing by every day and disappearing in the depths of the unconscious, Szczypiński searches for a point of reference, for certain constants, which have been ruling the world for ages, and which delineate the sinusoid relentlessly marking the path of art. Perhaps it is the right way to mark another point of reference after collecting all possible data?

Canon

Szczypiński claims that art history and its canon is a certain point of reference. It consists of a selected collection of canonic works; research methods which give us at least an impression of stability, irrespective of our individual tastes. They become fixed signs, holy commandments leading us into the sacred sphere of art.

In Szczypiński’s works, every once in a while, figures and compositions appear which refer to iconic paintings, to the canon of art history; such as “The Arnolfini Portrait” or “Madonna of Chancellor Rolin” by Jan van Eyck, Velazquez’s infantas, the images of Adam and Eve from Albrecht Dürer’s triptych, “Luncheon on the Grass” by Manet, or Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon”.

However, these are not copies of the original. The images are deformed, overemphasised or totally disintegrated and effaced. Sometimes this images are highlighted, sometimes only indicated. They frequently become almost abstract signs. In this way the artist draws from the viewers’ knowledge, their ability to associate and their imagination. In his latest works the artist takes a step further. In the 21st century, the notion of canon is rather more often associated with the canon of woman’s beauty than with the canon in art. The canon of beauty is nowadays often referred to the world of fashion; to the colourful covers of women’s magazines, to clothes and cosmetics adverts, or to the products and gadgets which are defined as “indispensable” in life. The canon gave way to secularisation, and has been annexed by the needs of a consumerist world and society.

The way of depicting a woman has also changed over time. In the nineties models were one of us – the mortals. However, the images that Szczypiński reaches for come from the seventies and the eighties as well as from the present, and have characteristic/specific sharpened features. A model’s face resembles a mask. She is supposed to be distinctly different from an ordinary woman. She has a certain statuesque artificiality. She is as a woman taken from the religious images of the saints – she is a Madonna from medieval sculptures, altars and frescos (Szczypiński uses Her images as well). This consciously over-stylised woman’s image in an advertisement places her within the same sphere of the sacrum that had inclosed religious depictions hundreds of years ago.

And so, in Mateusz’s works, images of models seamlessly turn into images of the Holy Mother. This can be indicated – as it is in the painting titled “MBC5” (the Holy Mother of Częstochowa, also known as The Black Madonna of Częstochowa) – by using solely two pairs of eyes emerging from the emptiness and darkness, or by tightly filling the canvas surface with images of models. In the second case they resemble figures which make up the background of medieval religious imagery; they become almost an ornamental decoration. They are ubiquitous and expansive. They are not an enigmatic sign of something mystical, but, with their possession of the canvas, they represent contemporary society’s materialistic, consumerist and bodily urge to possess.

Finally, we need to ask, what kind of image of the present is depicted in Mateusz Szczypiński’s works?

His paintings show a world in which everything has already existed, where everything is set in clear contexts, which determine our reception of their meanings. Everything is relative and possible in this world; the boundaries between a museum and a shop, between the interior of a flat and the interior of a church are blurred. The division between the sacrum and the profanum has lost its sense. Something that once belonged to the sphere of the sacred – such as the image of Holy Mary with Child, or the images of the saints – have been driven out of paradise; like Adam and Eve (otherwise appearing frequently in Szczypiński’s paintings), their images have become secularised. Nonetheless, there is still a hunger for rules, the need for a canon, a certain constant to which one can relate to and which is situated in the past, in history. History has canons, rules, trends and ideas that have not only inspired individual artists but generations as well. However, an objective canon is a tempting utopia not to be fulfilled in contemporary times.

There is no one truth and no one image of the present. Szczypiński is not interested in changes on a global scale. That is why he focuses on the things closest to us – “our matters” – paint, canvas, images that have been written into our consciousness, which accompany us in various forms, in the memory of the individual, in subjective perception and in belonging to a given culture.

words: Dobromiła Błaszczyk

[1] N. Bourriaud, The Angel of the Masses. The Use of Wreckage and the Rubble of History in Contemporary Art […] Historia w Sztuce/History in Art, MOCAK, Kraków 2011, p. 30.

[2] N. Bourriaud, The Angel of the Masses. The Use of Wreckage and the Rubble of History in Contemporary Art […] Historia w Sztuce/History in Art, MOCAK, Kraków 2011, p. 22.

[3] N. Bourriaud, The Angel of the Masses. The Use of Wreckage and the Rubble of History in Contemporary Art […] Historia w Sztuce/History in Art, MOCAK, Kraków 2011, p. 26.

[4] J. Błoński, M. Kędzierski, Samuel Beckett, Warszawa 1982, p. 113. (Excerpt from an interview with Tom Driver “Columbia University Forum”, summer 1961.)

[5] J. Błoński, M. Kędzierski, Samuel Beckett, Warszawa 1982, p. 113. (Excerpt from an interview with Tom Driver “Columbia University Forum”, summer 1961.)

[6] N. Bourriaud, The Angel of the Masses. The Use of Wreckage and the Rubble of History in Contemporary Art […] Historia w Sztuce/History in Art, MOCAK, Kraków 2011, p. 24. (Louis Althusser, Le Matérialisme de la rencontre)